Charlotte Chan, our very own Digital Marketing Executive, has introduced Fifty Five and Five to Wordle and told us why it’s been such a success. Here, we put her presentation into words (wordles?) and take a closer look at the magic behind the game.

Throughout history, men have found ways to declare their love for women. The Taj Mahal, a sprawling mass of white marble, set with diamonds and pearls, was initially commissioned by Emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his favourite wife.

Or take the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, complete with fronds of vegetation and rippling fountains. A gift from the King Nebuchadezzar to his wife Amytis, who was homesick for the mountains of Media.

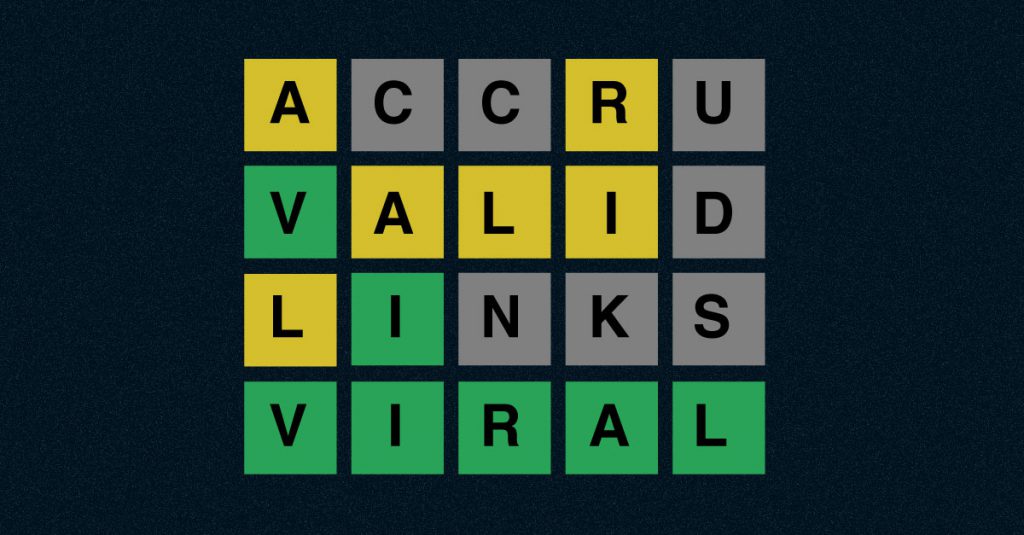

All heart-warming stuff. The modern example, and appropriate to our tech-centered agency, is Wordle. For those not in the know, Wordle is an addictive word guessing game, characterized by its colour palette grid of green, yellow and grey. For those in the know:

Wordle: a love story

I talk about love stories because it gives us an insight into how Wordle went viral. The game was crafted with love, for someone who simply loved word puzzles. It was built without a team of engineers, without a profit-making scheme (there are no ads), and without the frills that accompany most mobile games (prizes, levels, in-app purchases).

Wordle takes place on a simple 5x6 grid. The three colours each have a meaning (wrong character, wrong position on grid, and correct position). And, crucially, users can only play once per day.

The law of scarcity

That play is limited can explain, in part, how Wordle went viral. The game leverages a rule used by salespeople, marketers, and Tinder users worldwide - so called the law of scarcity.

The law of scarcity dictates that if something is scarce, people value it more. It’s often used in sales, usually for luxury brands (think jewelry, watches, cars), but technology companies also employ the tactic to generate interest in a product.

The law of scarcity underpins part of the magic of Wordle, despite it not being commercially designed. The game drives desire by limiting the amount people can play. It also feeds into an “app-aversion” mentality – the idea that people are averse to spending too long on a mobile app.

Cleverly, Wordle both limits addiction (by making the game scarce) and drives it by the same principle. Users feel like they’re not investing much time (even though they’re playing daily) and it’s this illusion which makes them invest more.

Put simply, Wordle is playing hard to get.

In with the in-crowd

Those who work in marketing will know that generating a piece of content that is “shareable” is difficult to achieve and cannot easily be contrived. It can be hard to predict what makes something popular, and it’s often things which buck a trend that do so well.

In December 2021, a few months after Wordle had launched, the game creator noticed that players were sharing their results by manually tapping out emojis (in the different colours), rather than sharing their score. The focus had turned to the little grid, and Wardle ran with this trend, incorporating this sharing technique into the game.

Shortly after, Wordle exploded in popularity.

The meteoric rise of Wordle can also – and this is an important point - be put down to its “shareability”.

Two lessons can be taken from the game’s "shareability” (and can explain how Wordle went viral). The first is that mystery generates curiosity. The colour grid on its own doesn’t make much sense, but since it kept cropping up on social channels, people started to take notice. The second is that people love being in-the-know. The wordle sharing sensation created an in-crowd, before its viral success, who enjoyed the novel way of communicating scores and felt part of a language-loving tribe.

Going off-grid

So, let’s get to the grid – the distinguishing feature of Wordle and what makes it so recognizable online. In a stroke of luck (and with a little tactical thinking from Wardle), the Wordle colour grid (and brand) has become instantly familiar.

To put this feat into perspective, there are only a handful of other brands that have achieved notoriety from their brandmark alone. The Microsoft window is one of them. The blue Twitter bird is another. Most brands require an accompanying wordmark to be recognized, and those brands which are visually familiar to their audience are typically market leaders.

That Wordle achieved this in under three months is impressive. Even more impressive – the grid is not officially Wordle’s logo.

The game might be all about words, but it’s the colour grid that’s generated so much buzz and, in part, explains how Wordle went viral. Reminiscent of ancient Aztec tiles or perhaps the top of a Rubix cube, each little grid tells a story – of success, luck, or struggle.

And brands have capitalised on this. Lego created the Wordle tiles as Lego bricks and shared on Twitter. IKEA imagined Wordle as a stack of drawers. Other brands, like Chelsea FC, used the single green line as a symbol of success in one try.

The grid, and the meaning behind the colours, tells a better story than words can. And this is the central paradox of the game.

Wordle might sell itself as a word puzzle, but this isn’t really its USP. The puzzle isn’t too difficult and correct guesses mostly come down to luck (with a bit of skill involved).

What’s really interesting about the game is that the colours show the journey involved. A mostly yellow grid, with a final green line, is a stroke of good fortune. A grid of sporadic green tells a story of frustration, struggle, and failure. Our ability to share results online inspires commiseration, congratulation and lots of Twitter memes.

A lasting love?

In January 2022, The New York Times purchased Wordle for a seven-figure sum. The Times announced that it remains free for players and promised to keep the game’s format intact.

That the game remains untouched is a good thing. Easy gameplay is part of Wordle’s appeal. So is its lack of a paywall, in-app purchases, and data collection. The game has a low maintenance relationship with its audience, making little demands of its players and never sending spam.

When we think about how Wordle went viral (and as marketers, the lessons we can take from its success), it’s likely down to a combination of shareability, scarcity, and ease of use. In an online world saturated with data collection and adverts – brands vying for your attention – Wordle’s opposite approach strikes a chord.

Whether Wordle continues to be a success under the auspices of The New York Times is yet to be seen – but it looks positive. There are currently millions of players sharing online. If The Times preserves its distinct features, as it has promised to, the game should continue to embed itself into people’s daily commute or bedtime ritual.

For some players, it may well be a lasting love.

Since 2021, the game has won the hearts of millions, and of one woman in particular – Palak Shah, the partner of software developer Josh Wardle (Wordle, Wardle – get it?) Josh knew Palak loved word puzzles and built the game for just the two of them.

Since 2021, the game has won the hearts of millions, and of one woman in particular – Palak Shah, the partner of software developer Josh Wardle (Wordle, Wardle – get it?) Josh knew Palak loved word puzzles and built the game for just the two of them.

By 2022, over 2 million users were playing the game.

Want to create a viral sensation?

Or just fancy challenging us on Wordle (we’re competitive – don’t take us up lightly!) At Fifty Five and Five, we produce smart content that gets shared. If you have a brilliant new idea, or want us to brainstorm one, just get in touch with our team.